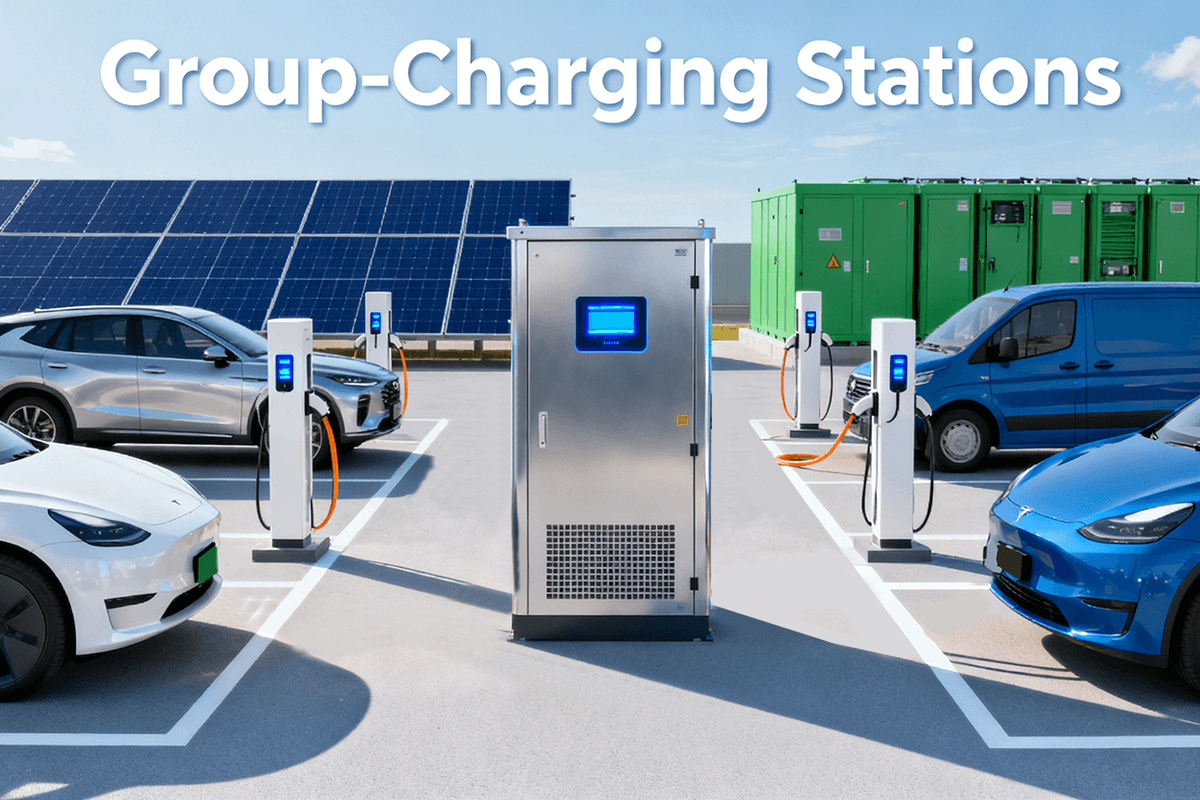

(Central power cabinet + multiple dispensers | Higher concurrency, shorter queues, steadier costs)

1) First things first: what is a “group-charging station,” and why build one?

In one line: A central DC power cabinet converts AC to DC in the back end, then shares that DC power on demand to several front-end dispensers (each dispenser serves one or more parking bays). Software handles dynamic power allocation. This “centralized DC” topology makes concurrency and remote operations (OCPP) straightforward, and it’s easier to plug into billing/reservations and other platform features (OCPP is maintained by the Open Charge Alliance and is widely used; see the official page: OCPP 1.6 official page (https://www.openchargealliance.org/protocols/ocpp-16/)).

Core benefits:

·More cars in parallel: With the same site capacity, you serve more vehicles at once, cutting queues.

·Lower cost pressure: Combine on-site energy storage (ESS) for peak shaving with time-of-use tariffs to reduce demand charges and transformer stress (see the U.S. DOE’s AFDC primers on electricity costs and demand charges: https://afdc.energy.gov/).

·Smoother experience: The system prioritizes power based on who needs it most, who will finish soonest, and each vehicle’s accepted power—reducing the “one idle bay while others wait” problem.

Think of it like one kitchen (power cabinet) + many serving windows (dispensers): the heavy cooking is centralized, and the front counter serves faster.

2) Who should consider group charging?

·Logistics parks / last-mile fleets: Shift-change top-ups with a goal like “get many vehicles to usable SOC within an hour.”

·Campuses / bus taxi depots: Peak arrivals in short windows; concurrency solves the queue problem.

·Ports / mines / highway hubs: Heavy duty or en-route fast top-ups require higher power and stable thermal performance. If you plan for heavy trucks, pre-provision MCS (Megawatt Charging System) in civils and interfaces for a smoother future upgrade (CharIN MCS overview (https://www.charin.global/technology/mcs/)).

3) How it works (ultra-short version, with traceable references)

1.Central rectification: The cabinet converts AC to DC (in the IEC framework, DC charging system and comms are defined in IEC 61851-23/-24; catalog: IEC Webstore — 61851-23/-24(https://webstore.iec.ch/)).

2.DC bus: Think of it as the main “soup pot” feeding all dispensers.

3.Dynamic allocation: Dispensers, cabinet, and vehicles coordinate via standardized messages; power flows to the vehicles that need it most and can use it best (vehicle/charger interplay relies on connector standards such as IEC 62196 and relevant regional protocols; catalog: IEC Webstore — 62196(https://webstore.iec.ch/)).

4.Concurrency shorter queues: As vehicles come and go, power follows the traffic, raising overall throughput.

5.Platform operations: Group-charging sites typically connect to OCPP platforms for remote monitoring, billing, reservations, alerts, and OTA updates (OCPP overview and docs: OCPP 1.6 official page(https://www.openchargealliance.org/protocols/ocpp-16/)).

4) Five steps to build a group-charging site (do these and you can launch)

Step 1 — Know your vehicles

·List your fleet’s voltage platforms (400/800/1000 V+), peak accepted power, and typical dwell times.

·Takeaway: don’t chase giant nameplates first—start with what the vehicles can actually accept (vehicle BMS limits by temperature and SOC; charge-control behavior is defined across IEC/GB/SAE frameworks—see the standards above).

Step 2 — Set a concurrency goal

·Write a one-line target: “At the peak hour, move X vehicles from A% to B%.”

·That line drives total cabinet capacity and number of dispensers. NREL’s fleet-electrification resources recommend sizing from vehicle needs and duty cycles (see NREL Fleet Electrification).

NREL Fleet Electrification: https://www.nrel.gov/transportation/fleet-electrification.html (https://www.nrel.gov/transportation/fleet-electrification.html)

Step 3 — Tier your power

·Make 150–180 kW your staple terminals; add a few 240–350 kW bays for urgent jobs or high-voltage models.

·For heavy trucks or long high-power sessions, prefer liquid-cooled 500–600 A cables(sustained high current with less thermal derating).

Step 4 — Power distribution + storage

·Utility transformer → LV switchgear → power cabinet → dispensers. Keep protection and routing clean and documented.

·ESS for peak shaving: Let batteries carry the spike and recharge off-peak; this lowers demand charges and eases grid impact (NREL case studies consistently show the value of peak shaving).

Step 5 — Layout & maintenance

·Drive-through bays, overhead booms/retractors, and clear service aisles.

·In hot seasons, keep filters/air paths clean to minimize thermal derates. Track availability, wait time, and derating events as station KPIs (your OCPP/CSMS or BI can export these metrics).

5) How to choose “power” (newcomer-friendly rules of thumb)

A single vehicle faster ≠ always bigger nameplate. The same car on 180 kW vs 240 kW may charge at similar real power because the BMS limits current by temperature and SOC and naturally tapers at high SOC (CC-CV). This behavior is described in mainstream standards and OEM white papers (see the IEC catalogs above).

A faster site = more vehicles fast at once. Four 150–180 kW bays often beat one 600 kW bay for total throughput and shorter queues.

Hot weather + long high-power sessions: go liquid-cooled; 300 A air-cooled cables are more likely to derate in extreme heat.

Planning for heavy trucks: if 1 MW class charging is on the roadmap, reserve MCS civil and electrical capacity now (see CharIN MCS overview).

6) Three reference deployments (easy apples-to-apples comparison)

|

Scenario |

Cabinet capacity (example) |

Dispensers |

Cable/cooling |

What to focus on |

|

Fleet/campus concurrent top-ups |

720–960 kW |

6–12 dispensers at 150–180 kW (mix CCS2/GB/T as needed) |

Air-cooled |

Dynamic allocation + reservations; ESS 200–400 kWh for peak shaving |

|

Urban shift changes |

960–1200 kW |

8–12 dispensers, with 2–4 at 240 kW for urgent jobs |

Air + liquid mix |

Keep high-power bays for peaks; use off-peak to top up everyone |

|

Ports/mines heavy duty |

1–2 MW |

6–10 dispensers at 300–500 kW |

Liquid-cooled first |

Higher ingress protection (IP54/55/65 by model), shade/dust control, local spares |

7) Where budget delivers the most value

Spend on concurrency + stable thermal performance before chasing one ultra-high nameplate.

Evaluate with a 3–5 year TCO: energy + demand charges + civils/electrical + maintenance + downtime. NREL’s fleet-electrification pages outline sizing and cost drivers clearly, and DOE/AFDC offers non-technical primers on infrastructure and operations.

8) Pre-launch quick checklist

·Clear concurrency goal (e.g., “in 1 hour, X vehicles from A% to B%”).

·Terminals 150–180 kW as the base, a few at 240–350 kW for peaks.

·Liquid-cooled 500–600 A for heavy-duty/long high-power bays.

·ESS peak-shaving strategy + capacity sizing done.

·Layout includes drive-through, booms/retractors, service aisles, shade/dust control.

·OCPP/remote monitoring/billing/reports/alerts integration tested.

·Spares list + target MTTR defined.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.